A blurred image. A restricted post. A piece of art reduced to a cautionary warning. In the covert conflict between censorship and creativity, nudity has become a digital battleground.

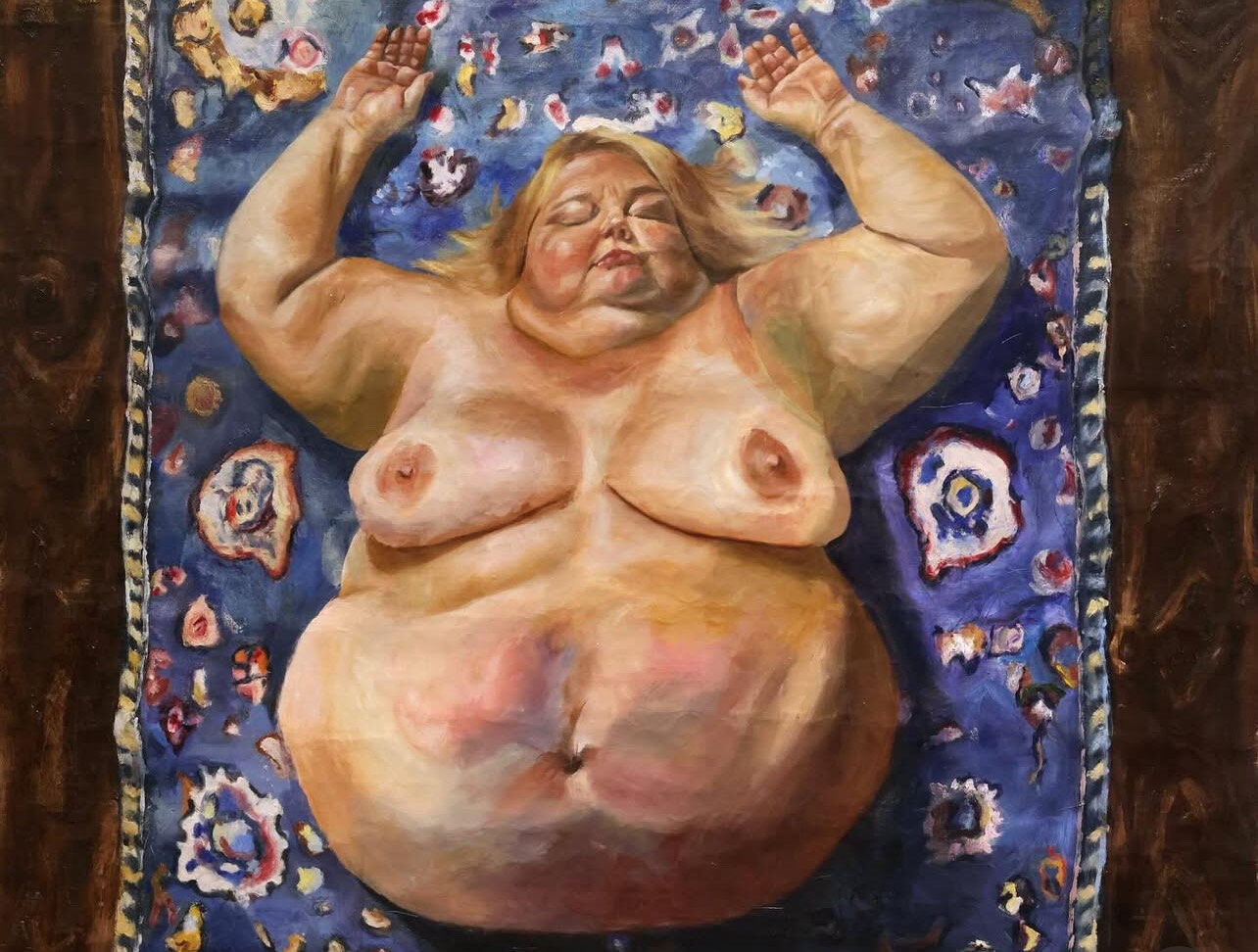

Nude art has played a fundamental role in artistic expression for centuries. It is celebrated for its ability to capture vulnerability, beauty, and the complexity of the human form. However, in the digital age, nudity remains a contentious issue, subject to both artistic admiration and strict censorship through algorithms and moderators.

Historically, nude art was a widely celebrated part of the cultural zeitgeist. In ancient Greece, the nude sculpture of Aphrodite of Knidos glorified the human body as a representation of harmony and physical beauty. In the Renaissance, nude art was taken to the intellectual and divine level by artists like Michelangelo with the statue of David and Botticelli with the birth of Venus. Both of these artists used the naked body not only for its unfiltered portrayal, but also to explore spiritual and philosophical ideas. However, during the Victorian era, nudity increasingly became moralised and hidden, associated with shame or indecency, while yet remaining a subject of fascination.

From the beginning, nude art has oscillated between reverence and repression, following the sociopolitical and religious values of the day. Contemporary controversies surrounding digital censorship are another chapter in this multifaceted and layered history, where ancient art traditions are at odds with today’s decency, consent, and control issues.

In a modern context, Felicia Beck, 19, an independent artist based across Europe, navigates a complex landscape where her work is celebrated in traditional art spaces but censored online:

“Instagram has shadowbanned me multiple times for my art,” Beck shares. “If you are an artist, remember that nudity in photos of paintings and sculptures is okay. Don’t let a platform silence your art.”

Much of this censorship stems from platforms’ reliance on automated moderation systems, which cannot distinguish between artistic content and explicit content. Leaked internal guidelines from Facebook reveal the challenges moderators face in discerning between “digital nudity” and “real world art,” acknowledging that the policy is “difficult to enforce because it is hard to differentiate between handmade art and digitally made depictions”.

These challenges are something that Grace Omole, 25, a life drawing teacher and artist based in Nottingham, knows all too well:

“Censorship impacts the engagement of my work; it’s difficult to reach new audiences with such outdated platform values,” Omole explains.

“Students in my classes always get mixed reactions to seeing a nude model and having to replicate the human form on paper. Much like social media, I assume, it’s conflicting.”

For Omole, the issue is compounded by race and representation as she focuses on the black male and female form in her work.

“As a Black woman creating art, it’s easy to be stigmatised. I focus on bodies that are often objectified or politicised in ways white bodies aren’t.”

“In my work, the line between objectification and empowerment must be monitored. Nudity doesn’t equal porn, and it’s not dangerous—therefore it shouldn’t be censored.”

Omole’s words provoke a deeper question about whose bodies are allowed to be seen on the internet, and how racial identity influences how that visibility is regulated. The lack of cultural sensitivity in censorship algorithms can mean marginalised artists face disproportionate barriers when sharing their work online.

As a response to these issues, artists and advocacy groups have taken action. For example, the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) organised the ‘#WeTheNipple’ campaign, pressuring Meta (Facebook and Instagram) to adopt more nuanced policies that distinguish between pornography and art. They argue that the current ban on photographic nudity disproportionately harms artists exploring issues of gender and identity and call for change.

“The female form has always been a source of inspiration for me,” Beck adds.

“Not just for its beauty, but for its power, resilience, and capacity to create life. Women deserve to be seen—not through a narrow gaze of societal ideas, but their most authentic selves: unfiltered, unapologetic, and deeply connected to their own essence.”

While social media has democratised art-sharing in unprecedented ways, it has also given policy teams and platform owners a monopoly of control, making it increasingly difficult for non-mainstream or boundary-pushing artwork to find visibility.

Legal frameworks are beginning to catch up, but not without risk. In the U.S., the Take It Down Act (2025), designed to combat the non-consensual sharing of intimate images, includes provisions that critics argue could also affect legitimate nude art or journalism. Similarly, the UK’s Online Safety Act (2023) requires platforms to minimise “harmful content,” a term which remains loosely defined and could be applied to sensitive but important artistic material.

This tension between artistic expression and digital censorship is emblematic of broader challenges faced by artists today. While platforms have community guidelines that claim to allow artistic nudity, enforcement often tells a different story. Instagram’s community guidelines state, “We know there are times when people might want to share nude images that are artistic or

creative in nature, but for a variety of reasons, we do not allow nudity on Instagram.” This has resulted in numerous artists reporting their content being removed or their accounts suspended.

“People who feel discomfort towards nudity and art should look at themselves and their own values,” Omole argues.

“Art is powerful, historical and important. It needs to be celebrated.”

Both Omole and Beck highlight how the digital space mirrors society’s larger discomfort with the nude form, particularly when it’s created by and for women, queer artists, or people of colour. As Beck puts it:

“It’s so funny how people are shocked when they see skin—even though we all share it. This is why I don’t understand censoring nude artists. We are all one in our skin, and it needs to be embraced and appreciated as an unfiltered truth.”

“I’ll always use the female figure as inspiration for my art. It’s so beautiful—no one can silence me.”

These voices are part of a growing resistance against cultural sanitisation, calling instead for a digital space that reflects the depth and complexity of the human experience. As platforms continue to shape how we share and consume art, the question remains: Can digital media evolve to protect both safety and creativity, or will artists continue to be victims of a flawed moderation system?

In a time when the human body is once again politicised, questioned, and policed, the nude returns to its most vital role—not as something improper, but as something truthful. And truth, in any medium, deserves to be seen.